the GUN INDUSTRY’S DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM is full of CRACKS

Every year, tens of thousands of firearms slip through the cracks of the legal market and end up in the hands of criminals. Gun trafficking is fueled by thefts from individuals and gun dealers, secondary private sales, and straw purchases, where someone buys a firearm for a prohibited person. Of the 2.3 million crime guns recovered by law enforcement and successfully traced back to a purchaser between 2017 and 2023, more than 48 percent — over 1.1 million firearms — were used in a crime within just three years of their initial sale, a strong indicator that they had been trafficked. And it’s another strong indicator, of many, that the gun industry isn’t doing enough to regulate its supply chain.1A “crime gun” is any firearm used in a crime or identified by law enforcement as suspected of having been used in a crime.

Gun dealers across the U.S. have contributed to the problem:

- Between 2016 and 2023, gun dealers reported that they had lost 72,776 firearms in 9,464 incidents. Over 20,000 of those firearms went missing in 2022 and 2023 alone.

- Gun dealers also reported that they had 46,072 firearms stolen in 7,140 incidents between 2017 and 2023. Over 11,700 of those firearms were stolen in 2022 and 2023.

- One gun dealer in Arkansas may have “neglected to record” sales for thousands of guns and was responsible for 98 percent of the state’s 2,951 missing guns in 2015.

- Six gun shops in Philadelphia sold more than 11,000 crime guns from 2014 to 2020.

- A single gun shop in Georgia sold more than 6,000 guns from 2014 to 2019 that were later recovered at crime scenes — more than half of that state’s crime guns during those five years.

Yet gun makers have resisted calls to better police their supply chains and stop working with dealers who sell guns that end up in criminals’ hands. For example, in 2019, in response to a shareholder-approved proposal for gun manufacturer Ruger to report on how it tracks information related to its products being used in crimes, Ruger executives placed the burden on law enforcement, claiming that it cannot “‘monitor’ the downstream use of firearms” through its relationships with distributors, and that the company “does not have visibility through the distribution channel.”

But Ruger offers sales promotions, reward programs, and awards to top–selling retailers “downstream,” and the company has even published figures on how quickly its products sell from distributors to retailers (known as “unit sell-through”) in earnings reports.

Industry Intel

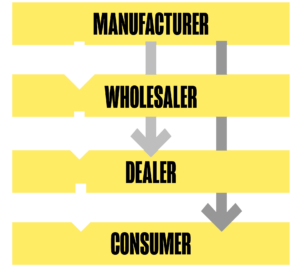

How Guns Get From Manufacturers to Consumers

Gun manufacturers produce firearms and sell them to wholesalers, who distribute and resell them to licensed dealers. Dealers include gun shops, sporting goods retailers, and individuals who sell weapons in person or online to consumers. Entities that make, import, and/or sell firearms and ammunition must obtain a federal license from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and follow federal, state, and local regulations before conducting any sale. In fiscal year 2023, the U.S. had over 132,000 Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs), including 50,309 gun dealers, 6,417 pawnbrokers, and 20,003 gun manufacturers.

While most gun makers do business with wholesalers, some work directly with “authorized dealers,” and an even smaller percentage offer direct-to-consumer sales, though customers will still have to pick up any firearms they purchase from an FFL after undergoing a background check or presenting a valid state permit qualified as a background check alternative.

The FIREARM SUPPLY CHAIN IS PLAGUED WITH PROBLEMS

While those “engaged in the business” of selling firearms are legally required to have an FFL, perform background checks on customers, keep records of every transaction, and undergo ATF inspections, federal law does not prohibit private transactions between unlicensed individuals or require that they involve background checks, providing an avenue for gun trafficking. Gun groups like the National Rifle Association and National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) — the firearms industry trade association, which counts over 9,000 gun makers and sellers as members and whose board consists of the largest gun manufacturers — also resist efforts to require background checks on all gun sales, alleging that the safety measure could lead to mass gun confiscation.

(In August 2023, the Biden administration announced a new rule that builds on the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act of 2022 to strengthen requirements for gun sellers to become FFLs and conduct background checks. The final rule went into effect in May 2024. Learn more here.)

Gun dealers must also notify the ATF when someone purchases two or more handguns (and rifles in states along the U.S.-Mexico border) within five consecutive business days, but there are no limits to how many firearms a person can purchase in a given time frame on the federal level. There is also no federal requirement for gun dealers to report suspicious customers, including straw purchasers, to law enforcement or even secure their stores — an obvious solution to preventing thefts, but again, groups like the NSSF have called efforts to require gun shops to lock up their inventories or install security measures “costly” and “burdensome.”

The FBI has just three business days to conduct a background check on a prospective buyer, but if it is unable to make a final determination to prohibit the transaction at the end of that time period, FFLs can complete the sale in what is known as a “default proceed” or the “Charleston loophole,” as it’s what helped arm the mass shooter who attacked a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. During the pandemic, the FBI needed longer than three days to complete over a million background checks, meaning those prohibited from owning firearms may have been able to walk away with them. Of course, thorough background checks take time, but this is another area where the gun industry prioritizes sales over security.

Some states have addressed these issues by requiring background checks on all sales, limiting how many firearms residents can purchase every month, closing the Charleston loophole, and establishing mandatory waiting periods before a gun sale can be finalized, for example. Yet problems persist.

FFLs hold onto sales records (as do some states, but not the federal government), which is why the ATF must often contact gun makers or search their records electronically to begin the process of tracing a crime gun through the supply chain, from top to bottom. As mentioned, however, gun manufacturers insist — despite being in possession of these records and receiving outreach from law enforcement — that they cannot track crime gun traces or monitor what happens to their products downstream.

Because of this system, between 2017 and 2021, nearly 100,000 crime guns were unable to be traced because dealer records were simply missing.

The ATF is tasked with inspecting FFLs to ensure they are properly maintaining records and legally conducting gun sales, but the chronically under-resourced agency inspected just 6.6 and 7.5 percent of all licensees in fiscal years 2023 and 2024, respectively, down from the pre-pandemic “high” of 10.1 percent in 2019, and before the Biden administration, developed a reputation for letting repeat offenders off the hook. In other words, gun dealers might go years without seeing an inspection. As one company that helps people obtain FFLs claims in the FAQ section of its homepage, “Typically, the ATF only inspects every 5-7 years.”

The Biden administration provided the ATF with greater resources and tasked it with revoking the licenses of “rogue gun dealers that willfully violate the law” by transferring a firearm to a prohibited person, failing to run a required background check, falsifying records, failing to respond to an ATF tracing request, or refusing to permit ATF to conduct an inspection in violation of the law. The “zero tolerance” policy, as it was known, led to more inspections and license revocations — and drew the ire of the NSSF, which took credit for having the second Trump administration rescind the policy.

The completed inspections paint a grim portrait. Nearly 18 percent (1,689) of all FFL inspections in fiscal year 2024 uncovered violations of federal law. The most common violations included:

- 37,654 instances of FFLs failing to maintain accurate inventory records (a 12.3-percent increase from FY 2022), meaning firearms may have been unaccounted for;

- 32,068 instances of FFLs failing to complete required forms (a 43.7-percent increase from FY 2022);

- 20,767 instances of FFLs failing to complete Form 4473 transaction records (up 12.1 percent from FY 2022); and

- 4,772 instances of FFLs failing to report multiple sales of handguns (up 8.3 percent from FY 2022).

Each of these violations can make it harder for the ATF to trace crime guns back to their first point of sale and disrupt trafficking rings.

Other violations, including failing to run a background check, can be found in this database of 2,000 inspection records from 2015 to 2017, as well as the ATF’s data on the gun dealers and manufacturers who had their licenses revoked in recent years.