Since the 1800s, most gun advertisements in America have been tailored towards men — showing men as powerful, masculine, and patriotic when they’re armed. But a 2024 study published in the Journal of Macromarketing found that over the past two decades, as gun manufacturers have sought to compete in a saturated market and diversify their customer base to include more women, some have moved away from objectifying them in advertisements to portraying them as competent users of firearms.

According to the researchers, the shift in marketing strategy can be explained by gun makers “finding…empowerment more effective in driving sales.” They also note that gun makers often depict women carrying guns — overwhelmingly pistols — for protection in their ads to capitalize on the expansion of concealed-carry laws after the Supreme Court’s Heller decision.

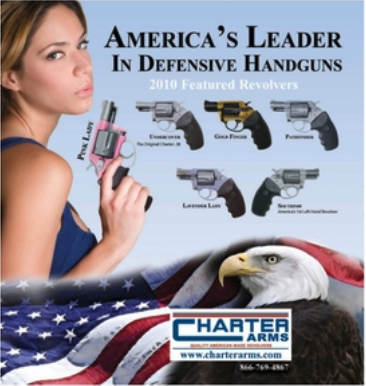

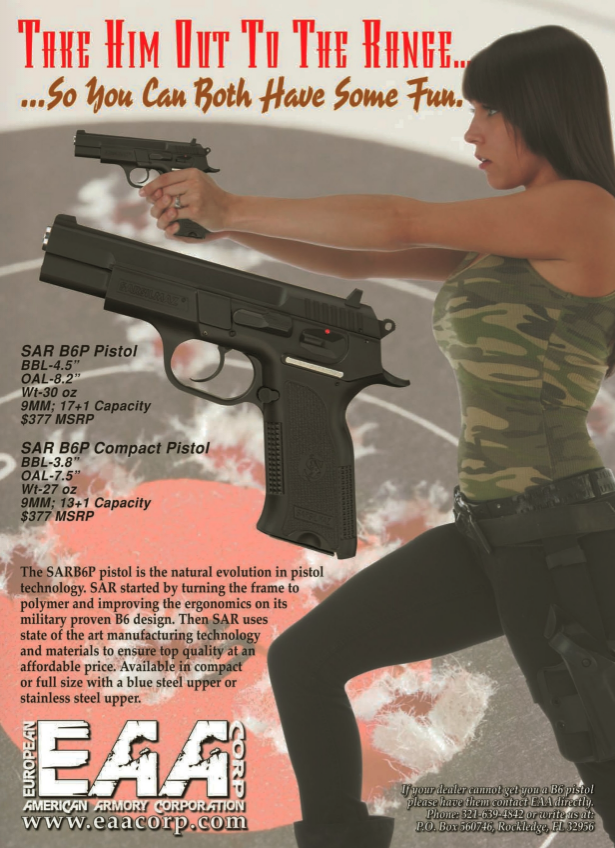

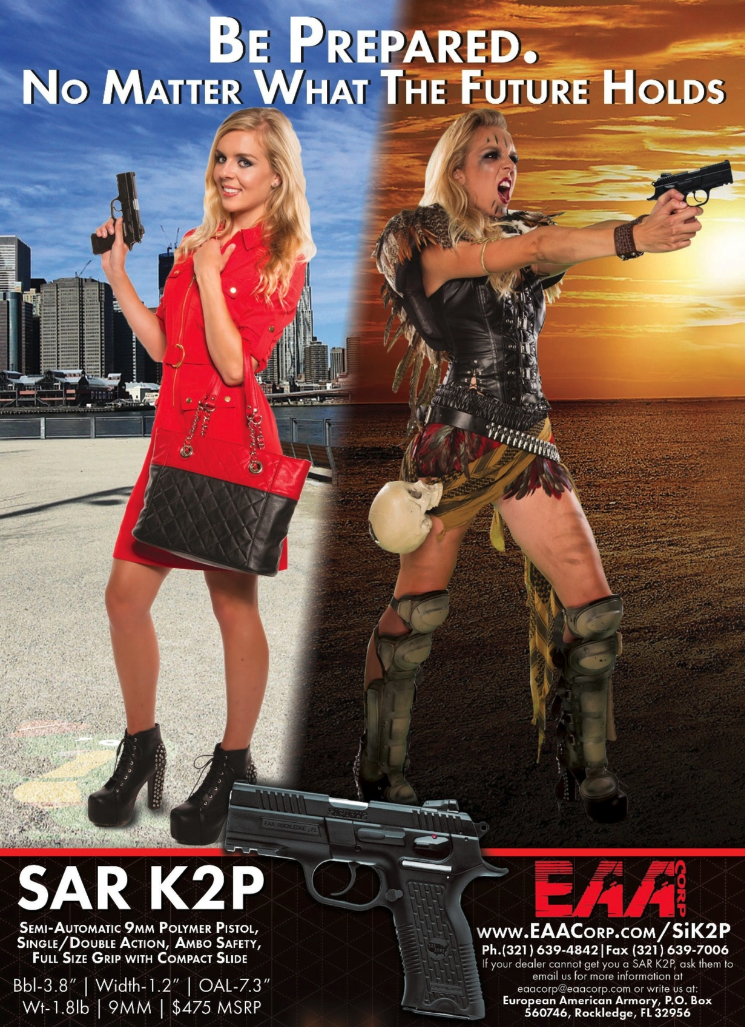

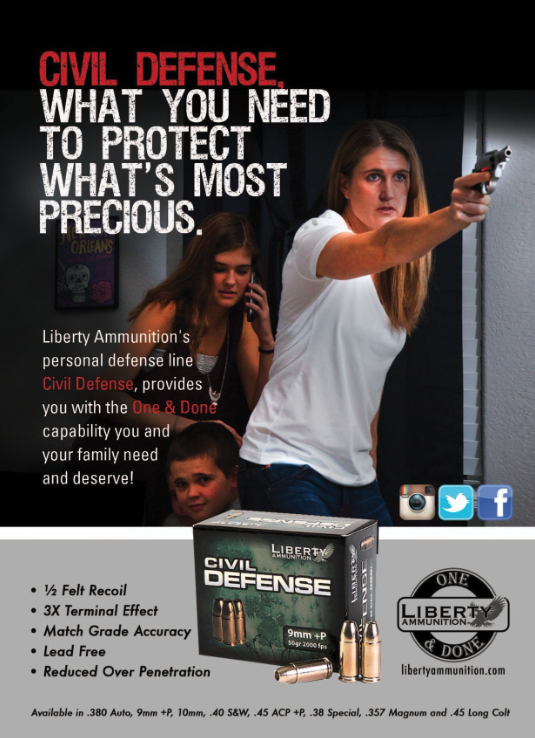

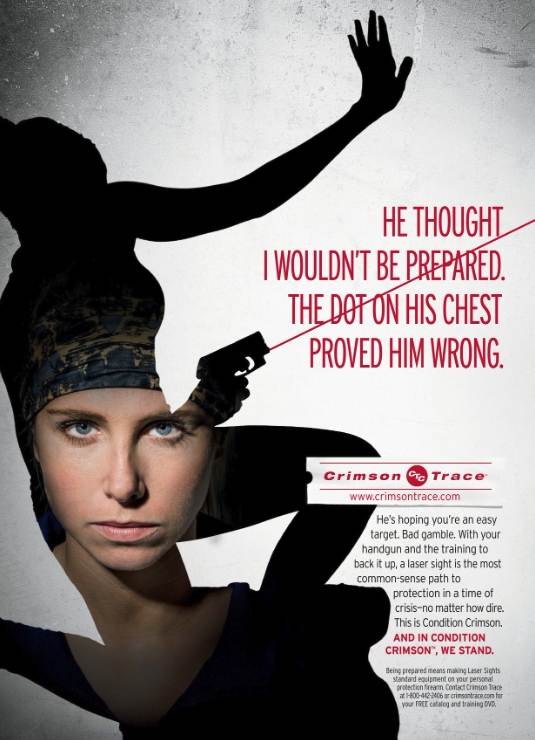

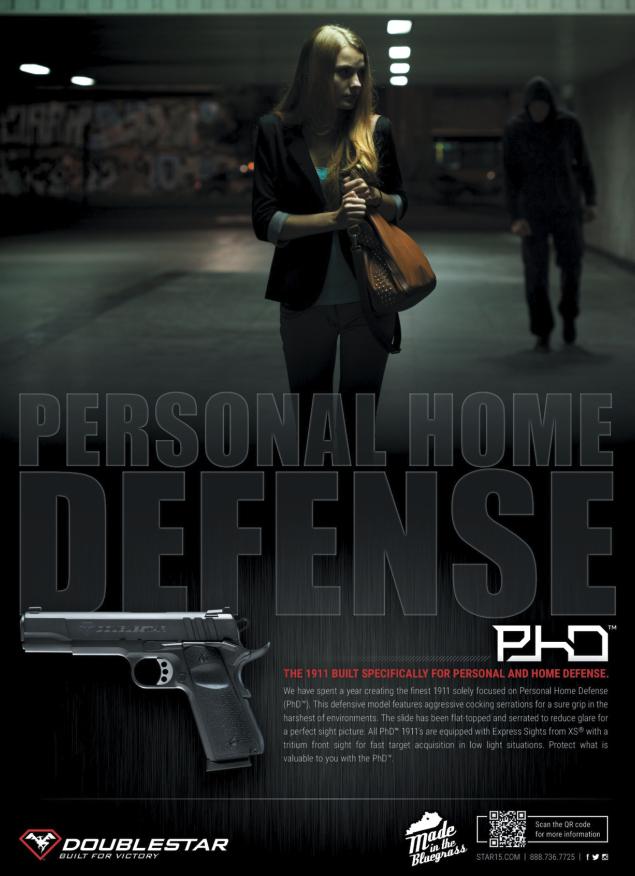

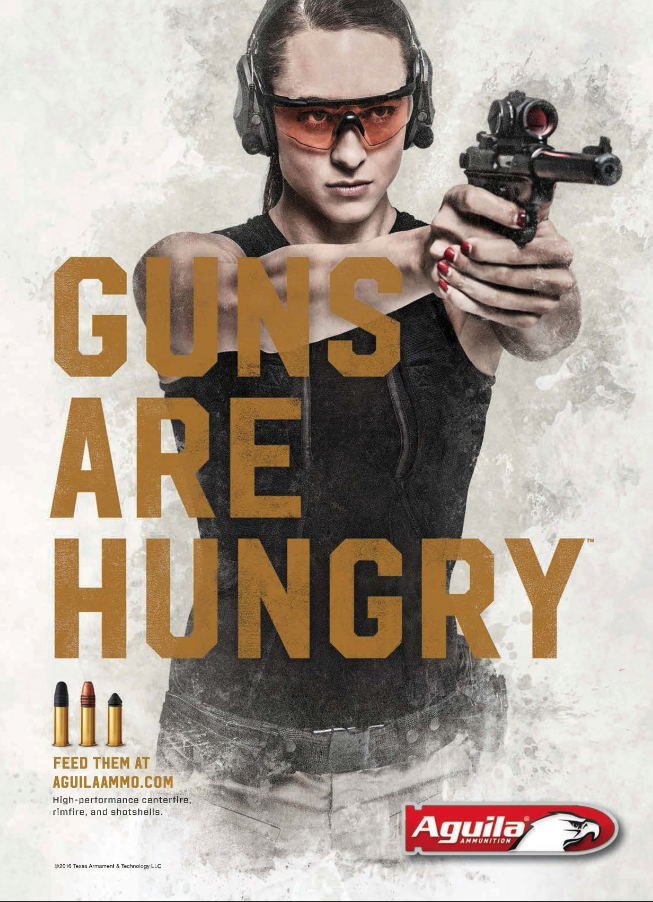

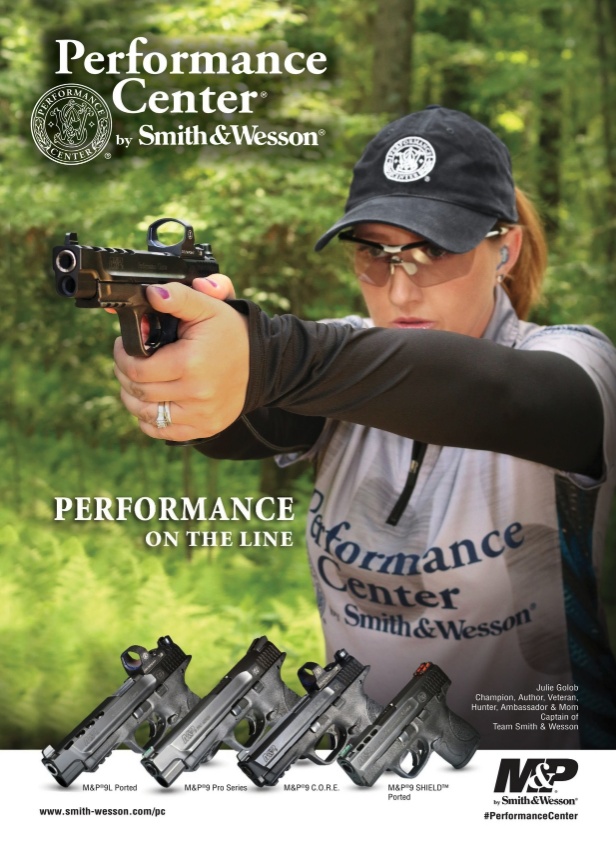

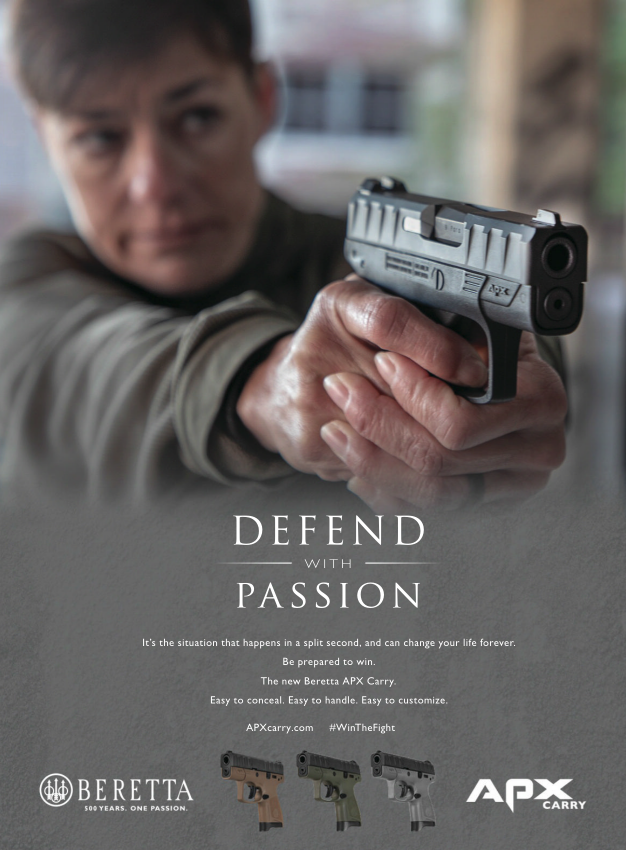

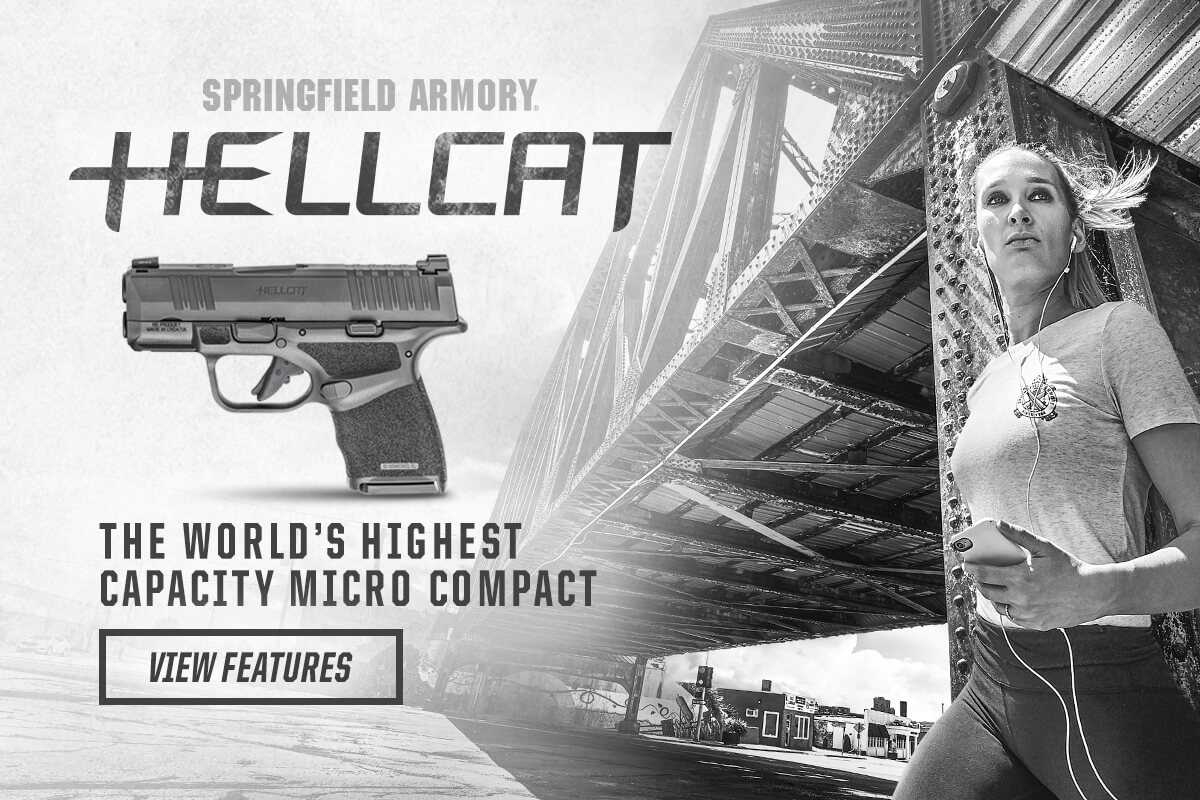

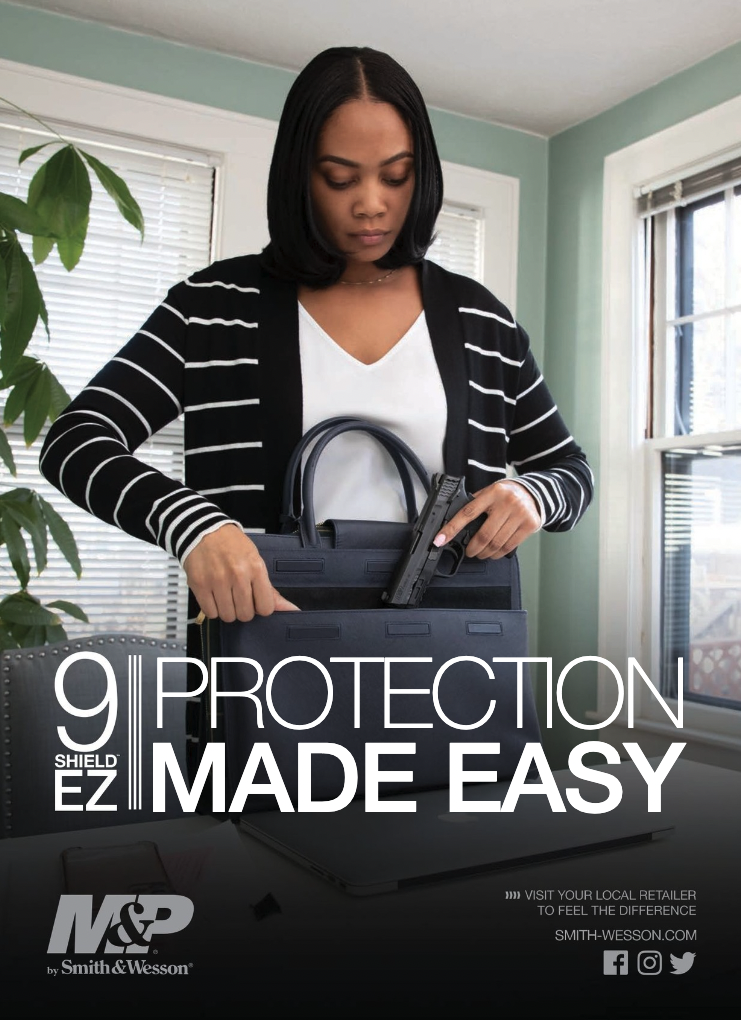

examples of gun ads featuring women

To learn more, we reached out to the researchers, three professors for Oregon State University, who have been studying guns in America for 10 years. Dr. Michelle Barnhart and Dr. Aimee Dinnín Huff are associate professors of marketing who study consumer and societal wellbeing and controversial products, respectively, and Dr. Brett Burkhardt is an associate professor of sociology who studies public policies related to crime and justice.

Dr. Barnhart and Dr. Huff also spoke about their 2024 study in Marketing Theory examining how gun influencers, or “gunfluencers,” depict gun ownership and “2A” ideology as a pathway to attaining status and self-worth.

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

Tell us more about your “Armed American Woman” study.

Dr. Burkhardt: In this study, we wanted to learn more about how women have been depicted in gun advertisements over the years. We focused on print ads in Guns & Ammo magazine, looking at issues from 2001 to 2020.

We learned a few interesting things about the gendered nature of this advertising. First, these ads only rarely featured women, and that was especially true in the early 2000s. Second, women who did appear in ads were most often depicted with handguns, which were implicitly or explicitly linked to concealed carry and self-defense. Third, we identified some new “types” of women depicted in the more recent ads, such as the “Serious Student,” a woman who develops firearms expertise through rigorous training, and the “Capable Carrier,” an armed woman ready and able to defend herself and family.

These new and more common depictions of women and firearms are examples of how the industry is seeking to naturalize women’s gun ownership.

What were you surprised to learn?

Dr. Burkhardt: I was struck by just how rare it was for ads to include women. In the 2000s, it was common to read through entire issues of Guns & Ammo and not see women in any of the ads for firearms. The fact that we now see women in these ads, and portraying different “characters,” demonstrates the industry’s efforts to increase ownership among women.

Your study notes that more gun makers are showing women as competent users in their ads instead of objectifying them. Why the shift?

Dr. Barnhart: They have shifted tactics largely in response to changing regulations. The gun industry made several attempts to reach women over the years. For example, in 1989, Smith & Wesson launched its LadySmith handgun line and advertised it in magazines like The Ladies Home Journal. At the time, there were more restrictions on handguns than we have today, and the industry’s marketing efforts didn’t lead to large increases in sales like what we’ve seen in the last few years.

Regulations started to change dramatically in 2008, when the U.S. Supreme Court reinterpreted the right to bear arms as an individual right to self-defense. It seems that as states began to expand consumers’ legal right to have, carry, and use handguns for self-defense, the industry seized on the opportunity to sell the idea of armed self-defense to what was still a relatively untapped market of women. After a few years of experimenting with sexualized ads that didn’t correlate with increased sales to women, the industry now seems to have landed on an advertising idea that works: showing women as competent and serious gun owners.

Do gun advertisers still struggle to frame their ads in a way that is respectful to women?

Dr. Huff: Yes, gun advertisers continue to face significant challenges in effectively framing advertisements for women. Advertisers, who are predominantly male, must balance portraying women as competent, legitimate, responsible gun owners with continuing to appeal to their traditional (male) audiences by emphasizing that gun ownership is inherently masculine.

A tension arises because if an armed woman is depicted as too masculine and tough, her femininity has been compromised. And if she’s too feminine, she comes across as silly, or perhaps sexualized. Advertisers also need to address specific concerns women have about firearms, such as size, weight, and concealability. Additionally, advertisers often struggle to represent women’s motivations for gun ownership, which are often more pragmatic than symbolic.

There isn’t yet an established female American gun owner identity or image that consumers can latch onto. Many ads still rely on gendered assumptions rather than a nuanced understanding of the different types of relationships women have with firearms.

Why aren’t there more gun advertisements depicting women as soldiers or police officers?

Dr. Huff: Gun advertisements rarely depict women as soldiers or police officers because these professions are understood as hypermasculine in American culture. Military and law enforcement imagery appeals to male consumers by reinforcing the connections between guns and authority, dominance, and institutional power. Showing women in military or law enforcement roles might emasculate these professional domains and potentially alienate core male consumers. Instead, advertisers frame women’s gun ownership through more socially acceptable lenses like personal protection and family defense. This approach allows the industry to expand its market to women without challenging the fundamentally masculine nature of gun culture.

Your study notes that gun advertisements for women are less overtly political. Does the gun industry’s entrenchment in politics make it harder for gun makers to reach women customers?

Dr. Burkhardt: Gun makers do face a challenge in appealing to women. That’s because women are more likely than men to support gun safety measures, and that’s true for gun owners and non-gun owners. Those preferences are at odds with NRA and GOP positions and talking points, which seek to expand gun access and limit regulations. Given this conflict, gun makers may find women customers to be more receptive to ads depicting women as “capable carriers” and “serious students” and less receptive to ads that portray women as players in a political struggle for freedom and Second Amendment rights.

Your research shows that gun advertisements directed at women often use fear-based imagery, showing women alone or with their children in dark parking garages.

Dr. Huff: These types of ads tap into a sense of vulnerability and heighten the viewer’s perceived risk. Ads like this strategically amplify women’s existing safety concerns by presenting worst-case scenarios — dark parking garages, home invasions — as imminent threats requiring continuous readiness for armed response.

Gun advertising has intentionally constructed a narrative where danger lurks everywhere, consumers need to be hypervigilant, and firearms offer the only viable response to fear of being victimized. This manufactured fear is particularly manipulative because it exploits women’s genuine concerns about safety while obscuring realities about violent crime rates and about firearms’ effectiveness for protection.

Your study mentions the NSSF’s market segmentation studies calling prospective buyers “Anxious Aarons” and “Debbie Defenders.” What do you think of those?

Dr. Barnhart: Given that survey data show that most gun owners cite self-defense as the primary reason they own a gun, it’s not surprising that the NSSF has identified market segments whose primary motivation is self-defense. While the names may seem a bit silly, they do tap into characteristics that are troubling. Specifically, the names highlight that these consumers feel vulnerable and are looking for some way to keep themselves and their families safe. The gun industry presents firearms as the remedy to this vulnerability.

Unfortunately, death and injury statistics going back to the mid-1990s have consistently shown that having a gun in the home increases, rather than decreases, the chances of someone in the household suffering serious harm — especially the self-inflicted harm of suicide. In the case of guns for self-defense, statistics tell us that the cure the gun industry is offering is actually worse than the disease.

Professors Huff and Barnhart, tell us more about your study on “gunfluencers.”

Dr. Huff: That study looks at how gunfluencers promote a gun-centric worldview. We identify how they use digital platforms to produce and disseminate a consumption ideology around the Second Amendment using four curatorial tactics: glamourizing, demystifying, victimizing, and tribalizing. Their social media content shows Americans how and why to incorporate guns into an everyday lifestyle, and how to think about other people through this gun-centric lens. The gunfluencers illustrate an underlying consumption ideology: what’s right and wrong, the appropriate role of guns in society, how to understand other people as either pro- or anti-gun.

According to your study, gunfluencers glamourize and demystify guns, depicting them as status symbols and everyday objects, respectively. When you talk about victimization and tribalism among gun owners, what do you mean?

Dr. Barnhart: Many posts by gunfluencers emphasize the ways that society oppresses gun owners through unjust treatment, and how gun owners are constantly under threat of unjust regulation. For instance, a gunfluencer may post an image that they know pushes the boundaries of what’s allowed on Instagram, and if Instagram removes the post, the gunfluencer then posts an angry complaint about Instagram’s unjust treatment of gun owners. That’s what we mean by encouraging a sense of victimization. This goes hand in hand with tribalism. By posting content that encourages followers to view themselves as part of a like-minded group who must band together against this oppression, gunfluencers help to build and reinforce a sense of community among their followers.

Do male and female gunfluencers approach this content differently, especially in how they engage audiences?

Dr. Huff: We see distinct strategic differences between male and female gunfluencers. Female influencers more frequently emphasize educational content, positioning themselves as approachable instructors making firearms accessible to newcomers, particularly women. They often highlight personal journeys of gaining competence and confidence through training.

Male gunfluencers, conversely, tend to emphasize technical expertise, tactical applications, and political advocacy. While both groups employ lifestyle integration — showing firearms as part of everyday life — women more frequently address barriers to entry like gear fit, recoil management, and concealment options specifically for female bodies. Female influencers also more explicitly frame gun ownership as empowerment against potential threats, whereas male influencers more commonly invoke patriotism and constitutional rights.

Some gunfluencers start out with product reviews before transitioning to more ideological content. Is this a natural byproduct of gun groups sponsoring gunfluencers?

Dr. Huff: We speculate that the process could go either way. A gunfluencer may initially post reviews of guns or instructional videos, and then find that posting messages that advocate for the Second Amendment attracts more follower engagements. Or, they initially post about gun rights advocacy and gain enough followers that a manufacturer invites them to do a product review.

Is it dangerous for gunfluencers to normalize firearms and show them as everyday items?

Dr. Barnhart: Studies show that safe storage laws decrease death and injury, so it is reasonable to assume that treating guns as everyday items — that is, regularly carrying them or having them easily accessible outside of a safe on a daily basis — would lead to higher rates of death and injury. Glamorizing products tends to lead to increased consumption and normalizing their use. Given that owning a gun carries risk, increased consumption increases the chances that the risk will actually materialize for someone.

You mention that gunfluencers view banned content as a “badge of honor.” How can social media platforms moderate gun content without further fueling its appeal?

Dr. Huff: Social media platforms face a dilemma in moderating gun content. Their current approaches can create martyrdom narratives that gunfluencers leverage to strengthen in-group solidarity and demonstrate their “persecution” by platform users that report their content and by tech companies.

More effective moderation might require platforms to shift from reactive, keyword-based approaches to more sophisticated content analysis that distinguishes between educational content, enthusiast content, and potentially harmful or extremist gun content. One potential remedy is for platforms to develop clear, consistent gun-related guidelines that gun influencers understand in advance, rather than using seemingly arbitrary reactionary enforcement that fuels gunfluencers’ claims of bias. The goal should be moderation that’s perceived as fair and reasonable by most platform users.