Since 1968, the federal Gun Control Act (GCA) has required that licensed gun manufacturers imprint unique serial numbers on their guns’ frames and receivers, the basic building blocks of every firearm. The GCA also requires that gun makers, importers, and dealers — Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs) — log the serial numbers of firearms that enter and leave their inventories, so if a gun is later recovered from a crime scene, police can contact the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) to trace the gun back to its first point of sale. The ATF contacts the manufacturer or searches its records electronically, finds out where the gun was sold, and works down the supply chain to the dealer, because no federal authority maintains these records. The burden of record-keeping rests on the shoulders of FFLs, which is why serial numbers are so crucial to law enforcement investigations. Additionally, since 1993, federal law has required that FFLs perform background checks on non-FFL customers.

But in recent years, dozens of companies found a way around federal regulations to sell gun parts and do-it-yourself kits online and at gun shows that made it easy for anyone, including those prohibited from owning firearms, to build their own untraceable firearms at home in minutes. These “ghost guns” are made using so-called “80-percent”-complete frames and receivers sold with jigs, instructions, and even drill bits so that they can be finished quickly and without specialized training. More importantly, these unfinished frames and receivers lacked serial numbers and, until recently, the industry maintained that they did not have to be sold or transferred through licensed dealers with accompanying background checks.

Of course, the “80-percent” moniker is itself misleading, as these firearm components are nearly finished. For example, before it reportedly shut down, the largest manufacturer and distributor in this market, Polymer80, produced “80-percent” frames for Glock-style pistols that could be completed by simply drilling out three holes and removing four plastic tabs. After that, other parts, such as the slide and trigger, could be added to the frame to complete the pistol.

The rise of 3D printing has also opened another avenue for criminals to create untraceable firearms. While guns can be completely 3D-printed from plastic — like the single-shot, .22-caliber Liberator pistol that captured headlines in 2013 — today it’s more common for people to build sturdier firearms by 3D-printing frames and receivers and adding metal components, such as barrels and slides, made by established gun companies. The 3D printers, materials, and gun parts are all available online.

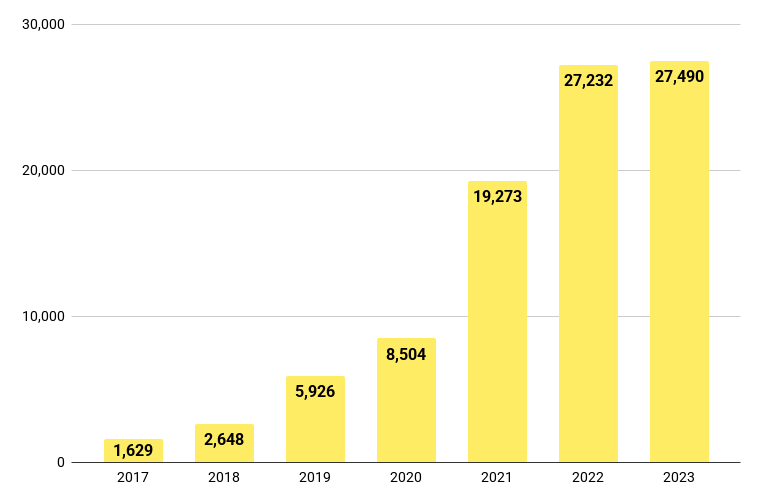

Predictably, ghost guns have emerged as the weapons of choice for criminals, gun traffickers, and others legally prohibited from buying firearms, leading to a steep increase in the number of ghost guns recovered from crime scenes in recent years, as depicted by the chart below. According to the ATF, police across the U.S. recovered 92,702 ghost guns (or what the agency calls “privately made firearms”) between 2017 and 2023. Additionally, the number of ghost guns recovered in 2022 and 2023 (54,722) was 44-percent greater than the total recovered in the previous five years (37,980).

Ghost guns have also been used in mass shootings, armed far-right extremists, and led to gunfire on school grounds in places like Arizona, Kansas, Maryland, and New Mexico. More recoveries and shootings involving ghost guns are detailed here.

ghost gun recoveries

The National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), the gun industry’s trade association, allowed ghost gun sellers like Polymer80 to exhibit at its annual Shooting, Hunting, Outdoor Trade (SHOT) Show. The NSSF even defended Polymer80 after the ATF raided the company on the suspicion that it was selling complete firearm-building kits without a background check as required by federal law, stating, “We have not seen credible evidence and statistics demonstrating that [ghost guns are] a significant issue.” And larger, more established gun companies continue to sell components for building, modifying, and repairing firearms — including ghost guns — online and through distributors. Some companies even sold Glock factory parts alongside ghost gun frames and kits, for example.

The frame and receiver rule

In May 2021, the Biden administration responded to this threat by proposing a new rule to end the proliferation of ghost guns. The rule sought to curb the ghost gun market by clarifying the regulatory definitions of “firearm” and “frame or receiver” to include ghost gun kits as well as standalone components like nearly complete frames and receivers.

The finalized rule, which went into effect on August 24, 2022, corrected the ATF’s previous interpretation of federal law. Since 1968, the federal definition of “firearm” has included 1) complete firearms, 2) those that are “readily” completed, and 3) the core building blocks of firearms, including the frames of handguns and the receivers of long guns. As the Department of Justice stated, the ATF’s new rule “makes clear that parts kits that are readily convertible to functional weapons, or functional ‘frames’ or ‘receivers’ of weapons, are subject to the same regulations as traditional firearms,” meaning they must be serialized and sold with an accompanying background check.

According to the final rule, the ATF will consider several factors in determining if an unfinished frame or receiver can be “readily completed,” including the time it takes to finish the process, the ease of doing so, and the equipment required.

In determining if a firearm part counts as a frame or receiver, the ATF “may consider any associated templates, jigs, molds, equipment, tools, instructions, guides, or marketing materials that are sold, distributed, or possessed with the item or kit, or otherwise made available by the seller or distributor of the item or kit to the purchaser or recipient of the item or kit.” In other words, the ATF can look at how a product is sold and marketed to determine if it is in fact a frame or receiver and needs to be serialized and sold with a background check.

the ghost gun market TODAY

After the final rule took effect, gun groups, state attorneys general, and ghost gun sellers, including Polymer80, levied lawsuits against the ATF and Department of Justice in an attempt to stop the rule from being implemented. Their complaints alleged that the ATF — tasked with enforcing gun serialization and sales requirements that have been on the books since the Gun Control Act was enacted in 1968 — does not have the authority to promulgate the rule. The U.S. Supreme Court has allowed the rule to stand while it is being litigated and, in October 2024, heard one of these challenges: Garland v. VanDerStok. To learn more about that case, click here.

For its part, the NSSF asked the agency to withdraw the rule, calling it “vague, ambiguous, confusing, ‘arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, [and] otherwise not in accordance with law,’” and claiming that the ATF had “exceed[ed] its statutory authority.” Notably, the NSSF has not put forth any alternative solutions to the growing problem of ghost guns.

Time will tell if the ATF’s rule is allowed to stand, giving the agency the power to investigate and shut down companies that continue to sell “readily completed” ghost gun parts and kits. Today, very few websites sell 80-percent frames and receivers or the jigs required to complete them. Some ghost gun sellers have instead shifted to offering 3D-printing files for frames and receivers along with the rest of the parts necessary to build untraceable guns.